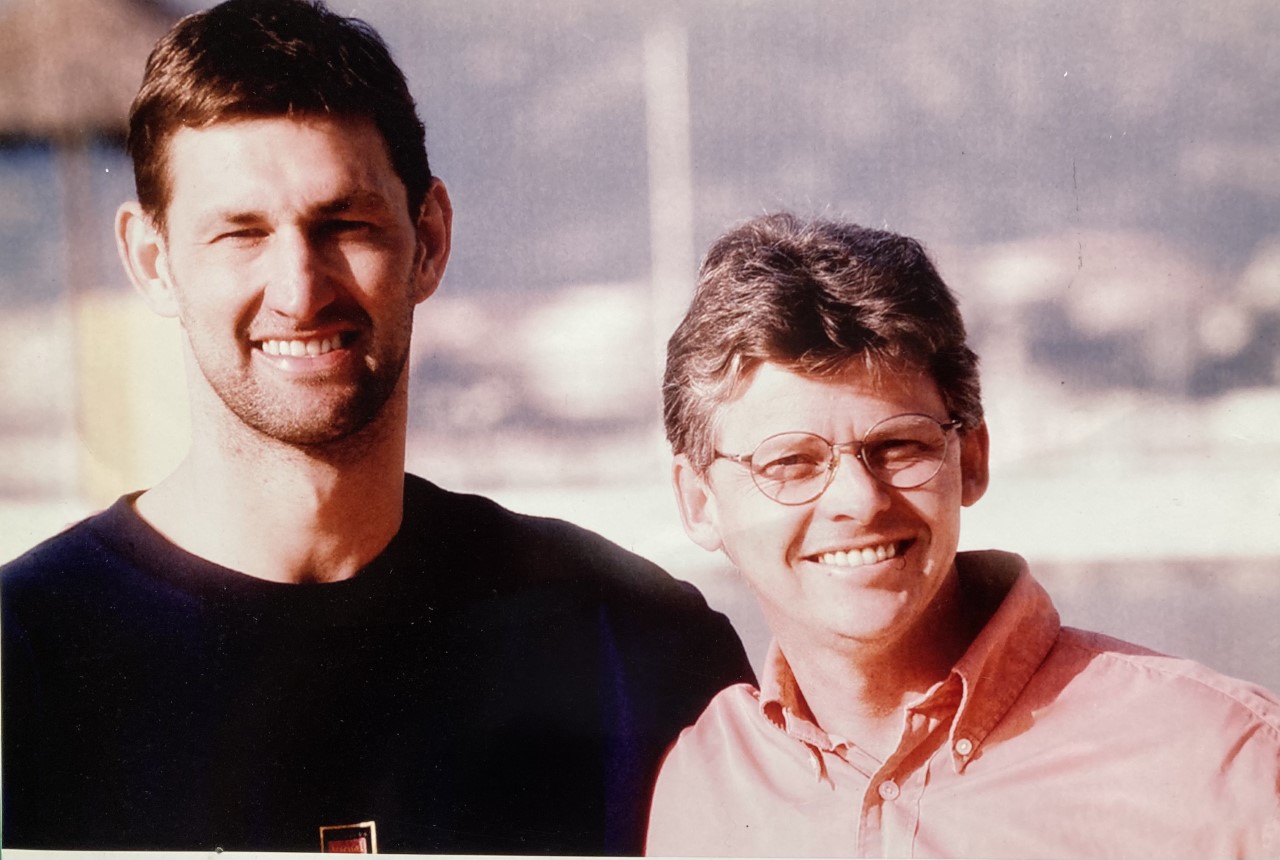

Floodlit Dreams publisher and author Seth Burkett is currently playing professional football in Sri Lanka. Throughout his time he’ll be blogging on the Floodlit Dreams website and writing a weekly column in the Non-League Paper. Below is an extract from his diary of the journey from Kalutara to Trincomalee, the city he’ll be representing in the North East Premier League.

22 players are on a bus to Trincomalee. We board at 9pm and are expected to arrive at 5am. It’s not a long way but it’s going to feel like it on this bus.

There’s no air conditioning. There’s no leg room. Anyone wanting to sleep has to contend with a toxic mixture of Pitbull and traditional Tamil music being pumped at full volume over the speakers.

Expense has been spared.

Me and Dean sit together at the front. His limbs are contorted into ridiculous angles as he attempts to fit into his window seat. This is going to be even worse for my legs than one of coach Kapuli’s sessions.

I dare not let go of my bag. Not for fear of it being stolen, but for fear of it falling out of the open door. We have two drivers and the co-driver prefers to stand at the door, hopping in and out of the bus every now and again. One hard turn and my bag will go flying.

We’re pretty much being dumped in Trinco. None of the others who will be staying with us are on this bus. Initially we were told we’d be staying at the owner’s house. Now we’re being told we are to stay at a hotel.

Before we boarded me and Dean were looking at each other frantically. What are we supposed to do when we get there? Where are we going? Where are we being left? Banda has now been tasked with taking us to our accommodation. The coaches will follow in a few days.

*

I’m still on the bus. My hamstrings won’t stop cramping up. There are still at least four hours to go. When you factor in the time lost to a punctured tyre, filling up, toilet breaks and pineapple stops it could be a lot more. I’m sweating so much.

*

This bus also keeps moving while passengers get on and off. The co-driver has just attempted to disembark and missed his landing, falling and rolling to the floor. We laugh, then check he’s ok.

He shakes it off like it isn’t the first time this has happened and returns to his position next to the open door.

*

As we get closer we wind through the towns and villages of Trincomalee district, dropping off players at various points. I expect to see poverty in the rural areas. I don’t. There are no decrepit shacks, only buildings of cement – admittedly small – that provide comfortable homes. Some towns are solely Muslim. The others have illuminated Buddha statues at their centre. There’s visible excitement when we cross Sri Lanka’s longest bridge, standing at 393m. My teammates are home.

*

‘Before the bombs, this road was full of white people.’ Priyan gestures up the track, allowing me to take in the stalls and the gifts and the juice bars that lead to the Koneswaram Temple. ‘Now, just you,’ he laments.

We remove our helmets and park the motorbike. Some of the stall owners attempt to lure me in, but most are resigned to defeat. Business has fallen drastically. The whole area is struggling.

Monkeys jump up and down on a parked tuk-tuk and scour the bins for food. We get close but not too close. Priyan warns me they’re dangerous.

Before entering the temple we remove our flip flops. This is a Hindu temple located in the naval base of Fort Frederick. It’s beautiful, it’s colourful decoration guarded by a thirty-three foot tall statue of Shiva. A stone indicates that the temple has stood on this very spot since 1580 BC. Few historical artefacts remain. The temple was destroyed by the Portuguese in 1622 as they raged war on the king of Jaffna by destroying temples and shrines throughout Sri Lanka. The vast majority of Koneswaram’s thousand columns and three stone temples disappeared into the sea as the Portuguese used the land to build Fort Frederick.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that the temple was rebuilt. The land, however, has remained spiritual throughout time. Pilgrimages take place regularly. But not since the bombs.

As we walk around the temple’s interior we’re joined by a small group who broken coconuts in half and used them to light a candle. Priyan tells me they’re doing so to ward off evil.

A tree at the back of the temple is covered with cradles. They’ve been hung by couples hopeful that Lord Shiva will give them a baby. Back around the front we linger at Lover’s Leap, where legend has it that Francina van Reed threw herself into the sea from after seeing her lover sailing off to Europe and breaking their engagement in the process.

Driving back down the hill we bump into Dean and Banda. They’ve just been pulled over by the police after Banda overtook another motorbike on a pedestrian crossing. The police officer was already halfway through writing a ticket for Mindron, who had Sakhti with him, when Banda attempted his overtake. Fortunately for Banda he knows the police officer. Mindron isn’t so lucky. He has no licence plate and has instead attempted to laminate a piece of paper with a few letters on. While all four players were getting a ticking off from the police officer, a confused and concerned coach Kapuli walked past.

Trincomalee isn’t a big place. It’s the kind of city where everybody knows everybody and all look out for each other. The sense of community is strong.

It’s a lot calmer here than in Kalutara and Colombo. It’s much more beautiful too. Boasting a natural harbour, the city is covered by water on three sides. White sandy beaches stretch for miles with clear sea water making it a perfect place for snorkelling and scuba diving. There’s no hustle and bustle. Nobody shouts. Stall owners sit and watch rather than stand and gesticulate. Cricket matches take place throughout. Dense green jungle land is everywhere. This is the closest I’ve been to paradise.

After visiting the temple themselves, Banda and Dean meet us on the beach. Sitting with ice creams and jackfruit nuts we discuss Trincomalee’s past and future. Priyan and Banda were just children during the civil war. Priyan lost both of his parents when he was one. His aunt brought him up. I don’t ask how they died. Both recall an incident that scarred the entire district: the 2006 Trincomalee massacre of five university students. Every night the five students would sit in the exact spot we are sitting in now and talk. One day the army drove past on the way to the naval base and shot them. There had been no provocation. The government claimed the students were Tamil Tigers and were about to launch a grenade but there was no proof. Two witnesses came forward to suggest otherwise. One, a photographer who took images to prove the army’s guilt, was murdered while the other has received death threats from the Sri Lankan security force. Thirteen years later the inquiry is still ongoing.

The city has a violent past but a bright future. Starting with the Portuguese destruction of the Koneswaram Temple and suffering sustained attacks from the Japanese in the Second World War and the Tamil Tigers in the civil war, Trincomalee has seen its fair share of destruction. Now it’s gripped by tourism. A burgeoning industry is developing. Or at least it was before the bombs. With such beautiful surroundings I’m not surprised.

Leave A Comment