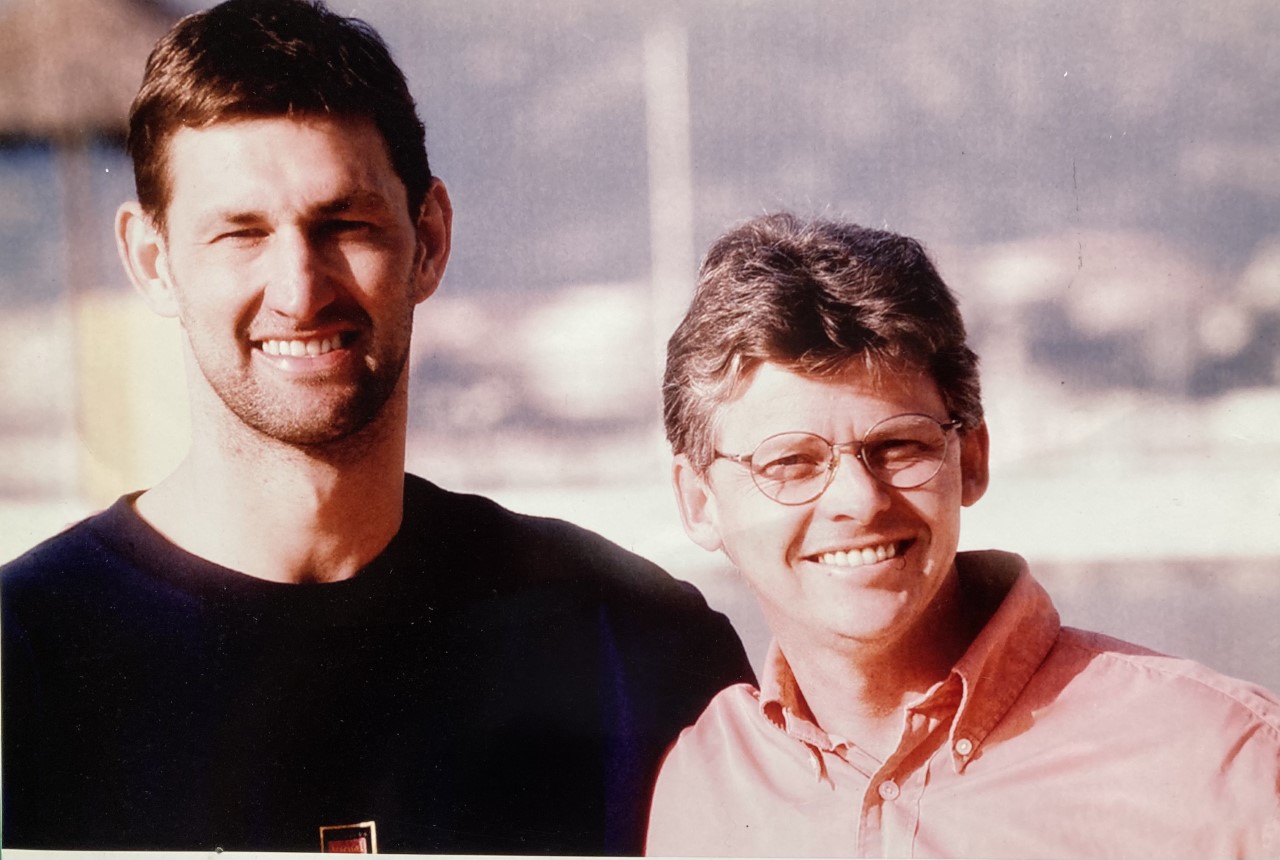

The Premier League have found a way to restart while the women’s game is left in a vacuum. Football writer CHARLOTTE HARPUR (above) analyses the state of no play

What a difference a year makes. In July 2019, 11.7 million people tuned in to the BBC to watch England play the United States in the Women’s World Cup. And yet, if an alien landed on Earth today, they’d be forgiven if they thought women’s football and, in general, women’s sport didn’t exist.

The Women’s Super League [WSL] and Championship [WC] were officially ended on May 25 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The finishing positions in the top two tiers were calculated on a points-per-game basis: Chelsea were declared winners, leap-frogging Manchester City, Liverpool relegated and Aston Villa promoted from the Championship.

However, points per game did not apply to other leagues. Instead, they were declared null and void with no possibility of promotion or relegation. Ipswich Town Women, their sights set on the WSL, would have been promoted to tier 3 and were understandably left frustrated.

“I spent weeks thinking after the decision ‘Why can’t they just promote us?’ ” says 18-year-old Blue Wilson, an Ipswich Town player and U18 England international. “Now seeing that the WSL and WC have done it on points per game twists the knife. There’s not much we can do. It’s done for safety and we were gutted when it wasn’t done on points per game. It sets us back a year.”

So why is it important to get women’s football re-started and what difference does a year make anyway?

Well, in the world of Covid, a lot. With fewer agents in the women’s game and short contracts, there are big decisions to make for young female footballers.

Adds Blue: “I’ve debated [what to do] ever since the league decision was made. I’m looking at other options of how to support myself. I’m going to be living in Ipswich so it’s getting a job, perhaps in accountancy, which fits around football, supporting myself to pay the rent, which is challenging at the minute because no one is hiring.

“We’ve got many young players who want to make something of themselves and haven’t got a long time to do that. A football career is short. These are the years when you prove yourself.”

Blue, along with all other WSL and WC players, are our future athletes. They deserve a platform and it is clear that more media coverage has the biggest impact. According to the FA, televised peak audiences for Barclays FA WSL have more than doubled but with the league set to resume on the 5-6 September and negotiations over the FA Cup and Champions League ongoing, it will be at least six months without the women’s game on our screens.

Visibility is essential. If there is no platform for women’s football, it’s as if it doesn’t exist.

Rebecca Myers, The Sunday Times Sports Reporter, explained at a recent webinar on The Future of Women’s Sport how she responds to the belief that it receives undeserving coverage. Her argument made a lot of sense: if we don’t know about women’s football, fewer people invest so the product cannot improve. If investment were there to improve the product, coverage would increase, which would attract larger audiences and bigger sponsors. This in turn increases clubs’ income and budget to buy players, which raises the product’s value and builds a greater platform. The cycle continues.

The lack of women’s football and therefore lack of visibility will affect participation at grassroots level enormously. We already know, according to Youth Sports Trust, that even by the age of seven, girls are less active than boys. That is why, in these times especially, it is vital that young girls have role models on TV, are shown that when it’s safe to play, they should too, and clubs dedicate the same amount of training time and pitch space to them as their male peers.

Will women’s clubs be able to survive?

The top two tiers will still receive £7m per year from the FA and the fact that Leicester City have recently agreed to invest in their women’s team is a step in the right direction.

However, clubs lower down the pyramid may have to think of other ways. For instance, Ipswich Women depend entirely on volunteers to run. In order to fulfil their goal of competing in the WSL, Ipswich need more staff to commit to more hours, to provide a better programme to attract talented players. This transition from voluntary to part-time costs money and with the parent men’s club uncertain of their own budget, there is no guarantee of funding for the women’s side.

“We’re taking it into our own hands”, says Blue Wilson. “We’re now looking at new sponsors and we’ve got a brochure to send to corporate companies. It’s all about sustainability.”

That is the crux of the issue. Can women’s football be sustainable in a period of economic recession and uncertainty? Only time will tell. What is certain is that Covid-19 will force change across the world and women’s football will have to be innovative in order to maximise its growth for the future.

*Charlotte Harpur trained as a French teacher in Northamptonshire. A discussion with pupils at break time about why there wasn’t a girls’ football team encouraged her to set one up and then to write an article about girls’ sport in schools. She submitted the piece and reached the final of the SJA Student Sportswriter of the Year competition. Charlotte has since written on a variety of sports for The Daily Telegraph and The Times. She has also enjoyed commentating on men’s and women’s football for BBC Radio Oxford and Northampton.

Leave A Comment