TEN years ago on August 12th, Weymouth Football Club lost their club President and stalwart Bob Lucas to prostate cancer, and Floodlit Dreams founder IAN RIDLEY, a former WFC chairman, lost one of his great friends and mentors.

Two years after Bob’s death, Ian went to visit Bob’s wife Jean for a chapter he was writing for a compilation of football writing entitled Life’s A Pitch.

Here, we republish Ian’s piece to mark the 10th anniversary of the passing of Bob, still much missed at Weymouth, who have recently been promoted to the National League’s top flight.

EVERBODY has a story worth telling, of a life lived with its hopes and dreams, dashed and fulfilled; of grand turning points and mundane moments, successes and failures. Jean Lucas doesn’t believe hers is much of a tale when I advance my theory to her. Not like Bob’s. But I think it is. Though supporting cast rather than leading lady, she played her own huge part in the life of the football club that took over my own life.

She is well prepared when I arrive. She has some old club programmes out, a magazine article about him, and the cosy council house is immaculately clean and tidy, as I expected. She is, after all, a woman of a working-class generation with standards, at odds from many of the modern families among whom she resides on the clearly recession-affected Littlemoor estate in one of the Dorset seaside town of Weymouth’s tougher suburbs.

She is not expecting me to say, however, that I want to talk about her as much as her late husband, Bob. “Get away,” she says. “I was always happy to be in the background, to do the gardening and look after the kids.”

Jean’s life, though, was always so touchingly intertwined with Bob’s, for the 59 years of their marriage that was shared with Weymouth Football Club, which he served with such dedication and distinction as goalkeeper, physiotherapist and president. In the end, so popular was he indeed, that they renamed the Wessex Stadium the Bob Lucas Stadium.

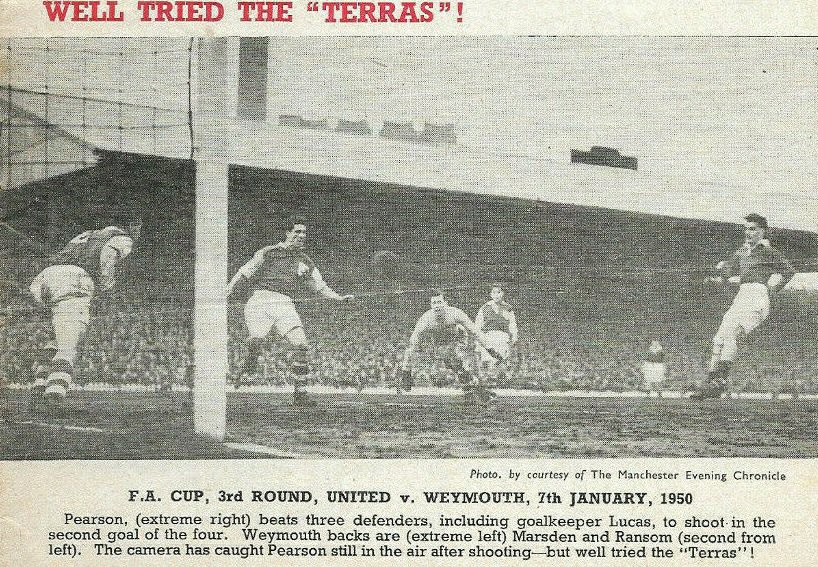

I couldn’t know him when he kept goal in the club’s most famous game in 1950, against Manchester United in the third round of the FA Cup – Old Trafford’s first Cup tie since finally being rebuilt after the War – and he was man of the match in keeping the score down to 4-0. I was five years away from being born.

I then got to know him noddingly, though, through the 30 years of him being physio of the club I have supported since childhood. Finally, I grew to know him intimately when he became club president in 2002 and I became chairman of the club a year later. Rarely has a relationship so enriched my life.

Such was Bob’s genial, supportive nature, his sheer pleasantness – and his role at the now empty heart of my footballing life – that I begin to fill up whenever I think about him in any depth. I have had heroes in football; Jimmy Greaves as a player, Jimmy Armfield as a man. No character in the game has ever had me both smiling and crying at his memory like Bob does. Did. I still struggle to get used to that past tense.

I couldn’t help weeping the night I saw Jean at the first Weymouth game following Bob’s death from prostate cancer in August of 2010 at the age of 85 and rushed over to hug her. Now we are both in danger of shedding a tear again as we remember fondly his life while sitting here in his old living room containing modest mementoes of his time at the club we both loved: a picture of him kneeling on the pitch, a cigarette lighter from the Football Association as recognition of his service as a physio for them; a plaque to mark his testimonial at Weymouth against Bristol City in 1998.

Bob Lucas was born on January 6th, 1925 in Bethnal Green, East London. Before him, his mother had lost three daughters to infant death, such was the severity of capital life in those days. At the age of 12, Bob was delivering newspapers in the morning and, after school, beer and spirits house-to-house from a barrow for an off-licence.

By 13, he had left school to help feed the family and got a job in a printing works. It paid him 7 shillings and 6 pence. After giving seven bob to Mum, it left him with a tanner, the cost of the boys’ enclosure at Tottenham Hotspur and Millwall.

When War broke out, the Lucas clan moved to Maidenhead after the family house was damaged in the Blitz and, his talent quickly spotted, he became Maidenhead United’s first team goalkeeper at the age of 16. Back in London in a new house a few months later, he was spotted playing for Golders Green and recruited for mighty Crystal Palace.

Active service as a radio operator in the Royal Navy intervened, though, and he spent three years in the Mediterranean, Atlantic and Far East before rejoining Palace in 1946. In his two years with them, he played four Football League games but wanted to get a job and play part-time, knowing he could earn more. The fear of financial insecurity, given his background, would never leave him.

He joined Tonbridge in Kent, where some Palace team-mates had gone to form a new club. There, a contact of the then Weymouth manager Paddy Gallacher saw Bob and recommended him. The club then helped him find a job with a printing company in the resort.

In 1949, Weymouth were just joining the highly regarded Southern League – as members of which Tottenham had won the FA Cup in 1901 before being accepted into the Football League – and needed a higher calibre of player. Bob fitted the bill. He made his home debut against traditional, fierce rivals from just across the Somerset border, Yeovil Town, in front of 10,497 – still Weymouth’s attendance recrod – at the club’s charming old Recreation Ground by the harbour before the concrete Wessex Stadium was completed in 1987.

He also made an impression that August, during his first week in Weymouth, on a pretty 17-year-old girl working in Harry Cole’s sports shop in the town centre, where he had gone to buy new boots. Jean Wheeler also made an impression on Bob. Soon they were stepping out.

“I was a quiet girl and was surprised he showed me attention,” says Jean, her smiling face recalling happy days. “He was my first boyfriend, the first man to show me any attention. He was quite a catch. Everyone in the town looked up to him. I came from a wooden bungalow in Wyke Regis. My family had no money.”

They married in March 1951, the wedding a big occasion in Weymouth. “I remember the pictures being on display in a photographer’s shop in the town,” Jean recalls. “There was a couple looking at them who didn’t know Bob and I were behind them. I remember her saying, ‘Fancy him marrying her.’

Was it not hurtful? “We just had a laugh about it.” It says much about the nature of both of them.

A year before the wedding came that FA Cup tie at Manchester United. The local paper, the Dorset Evening Echo, carried a picture of Bob phoning her from the hotel the night before the game. “He didn’t,” she confides. “We didn’t have a phone. It was just for the paper.”

She didn’t even get to the game, even though she was a Weymouth supporter, having been taken to the old ‘Rec’ by her father, who also ran, unusually for the times, a women’s team in the town to which the family had come from Devizes in Wiltshire when she was four, Dad having found work at the old Whitehead’s factory that manufactured torpedoes for the Navy.

Harry Cole, a club director, wanted her to stay behind and mind the sports shop while he went. She found out the score, and about Bob’s outstanding performance, from the ‘football final’ edition that the Echo brought out by 6pm on a Saturday night in those days. Some years later, as a kid in the 1960s, I would queue for it myself outside the paper shop, waiting for the van. Now some kids on a Saturday night seem to be waiting for the man.

Soon after getting married, printing work in Weymouth dried up for Bob after two years with the club – during which he once spent three weeks in hospital with a head injury after diving at an opponent’s feet – and he and Jean moved back to London to live with Bob’s mum at Mile End, where daughter Linda was born. Having found a job again with a printer off Fleet Street, Bob began playing for Ramsgate on the Kent coast. At the age of 28, he punctured a lung, however. Devastatingly, his playing career was over.

The smog of early 1950’s London, before the Clean Air Act, was damaging Bob’s breathing so they all moved back to Weymouth for the sea air. Bob became a bus driver for 10 years and watched plenty of local football as a scout for his contacts around London. Tragedy then struck the family when their second child, Bobby, died of cancer aged just four years and 10 months old.

“It was a very sad time,” says Jean, the pain hanging in the air. At the time, she was nursing young Bobby and Bob, who had suffered a recurrence of lung trouble.

Bob and Jean were heartbroken but football offered solace. Having become personally familiar with footballers’ injuries, Bob decided to train as a physio. Nearby Dorchester Town took him on and, once fully qualified, he also worked for the Football Association, who were impressed by his knowledge of new scientific techniques. He always was more than just a spongeman.

Not a manager, though. Dorchester put him in caretaker charge for a short while but he detested it. He could not really be firm with players, let alone ruthless.

He had to watch from ‘over the hill’ in the county town when Weymouth won the Southern League title in 1965 under Frank O’Farrell, who would go on to manage Manchester United, and then retained it the year of England winning the World Cup.

Then, in 1972, Weymouth took on a young player-manager by the name of Graham Williams, Welsh international left back who lifted the FA Cup for West Bromwich Albion in 1968. He came to this very council house that Bob and Jean had moved into in 1957 and asked Bob back to the club. Bob accepted readily.

After 74 appearances as a player, Bob would now go on to make a remarkable 1,948 “appearances” as a physio over the next 30 years, turning down offers of jobs in similar capacities at Bournemouth and Torquay United. He would see all the club’s ‘greats’ come and go; would treat them all. In the 1970’s, there was Jeff Astle of WBA and England at the end of his career; Graham Carr, father of comedian Alan and now Newcastle United’s chief scout, who would also later manage the club.

In the 80’s came the Alliance Premier League – now the Conference – and promising kids like Andy Townsend and Steve Claridge. Graham Roberts was sold to Tottenham for £35,000. The 90s were less successful, times for such as Darren Campbell, the Oympic sprinter who had a spell with the club before making the right choice of career, and local heroes like David Laws and Anniello Iannone.

In the end, by 2002 when he retired at the age of 77, Bob was on just £20 a week as physio, having taken a cut from £40 when the chairman asked him to help out as the club had financial problems.

It was no wonder he never wanted to buy the council house they were offered after Michael and Leslie became their third and fourth children. “He would never get into debt,” Jean explained. “That wasn’t Bob. We always rented.”

My acquaintance with Bob throughout those 30 years was mainly through my father, who had worked with him on the buses, and whenever I was back in my home town to see Dad, we would go to games, speak to Bob afterwards in the bar. Such is non-League football, where you can talk to anyone. We would bitch and moan, at the team and the board of directors. Bob would smile non-committally.

In the gossipy world of football, his discretion was what would surprise and impress me most when I took over as chairman in 2003, having offered my services and contacts to the club when they were at a low ebb in the Southern League. If he had nothing good to say about someone, he would say nothing.

When I first arrived, Bob came to see me. Characteristically humble, he asked if I wanted him to stay on as president. “I never take my position for granted,” he said. Of course I wanted him to stay on. Asking him to go would have been like ignoring the wisdom and demeanour of the Dalai Lama. It wasn’t just about anything he might have had to say. Often Bob only spoke when spoken to, even if when it did come it was always incisive. It was simply that the air of serenity and sense might rub off.

Weymouth, believe it or not, are a ridiculously introverted and political football club and I quickly became aware of it. A traditional non-League power – though further down the hierarchy these days with all the ex-Football League clubs populating the Conference – they will attract crowds of 1,500 if the team is doing well, as they did in my first season there when I appointed Steve Claridge as player-manager and he scored more than 30 goals as we finished runners-up in the Southern League to Crawley Town to qualify for the new Conference South. In that, a couple of years later, there would even be 5,022 for a title decider against St Albans City.

Anything less than top-class non-League football – with the aspiration of the Football League always in the background – would provoke fierce debate and criticism in pub, club and on rabid message board. The town was isolated geographically with few entertainments outside of the summer holiday season, and thus the club was at the centre of so many of the 55,000 population’s lives. The demands were so great, that even Claridge, veteran of Premier League and many intense outfits like Birmingham City and Millwall, said he had rarely come across a club with such high expectations.

Before my time were a group of local businessmen with their hearts in the right place but unable to turn a tide of decline. Once the playing fortunes had been turned round by Claridge, a local hotelier by the name of Martyn Harrison decided he fancied a piece of the action and after he took control, I departed. Harrison lost £3 million over two years in taking Weymouth to the verge of the Football League before pulling the plug and becoming ill in the process. He would pass away in 2012.

After him, came, briefly, a Bournemouth music promoter called Mel Bush, then a property developer named Malcolm Curtis, who shifted all the land around the stadium – some 10 acres – into the ownership of a development company, leaving the club land-locked and owning only its ground and no longer the adjacent training area or car park.

In 2008, at the request of two local businessmen who did a deal for control with Curtis (after one ludicrous episode when a potential buyer who turned out to be a cleaner from Torquay tried to acquire the club with a cheque for £300,000 that had Tipp-Ex marks on it), I returned as chairman for six months but was unable to solve the problems created by the new £750,000 worth of debt built up after Harrison. Then a man named George Rolls made Weymouth a staging post between his chairmanships of Cambridge United and Kettering Town, taking the club into administration.

Through it all, Bob had his own private thoughts and feelings about many of the characters and charlatans who came and went – and he would see some 35 managers and 16 chairmen in his 40 years of service, in the last decade of which more than 500 games as President took his involvement in first-team matches to well in excess of an astonishing 2,500.

There would be a glance here, a raised eyebrow there – a nod and a wink – but verbally he would always keep his counsel. He knew who were the good guys and who the bad, but he would also support the incumbent, always support the club.

There might be those who would see it as a sign a weakness, of a fiddling while Rome burned all around him as he declined to comment on some of those who had started the arson when his words would have carried much weight. Loyalty was his watchword, however. If he ever made a comment to me about a player, or an issue around the club that needed attention, it would be constructive and telling.

It meant that I, and probably all my predecessors, could confide in him with confidence, knowing I would not be judged badly nor my inner thoughts relayed to supporters or local press. It meant trust, a commodity that had become discredited at Weymouth and so short in modern football.

Above all, I saw Bob as the beacon of Weymouth FC’s honesty and integrity, as a symbol of what we should all aspire to. Amid the frequent chaos, bitter politics and twisted economics of the club, he represented probity and reminded us, me, of the goodness of men and the game to keep me fighting a good fight. At times, some of the club’s characters disgusted me. Bob reminded me of the importance of principles, and the club, above personalities.

I remember the day he told me he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer. I myself had been forced to leave Weymouth due to treatment for the same variety of the disease but they had caught mine early.

“I’ve left it a bit late,” he told me, by contrast. “I’ve been daft really. I thought getting up three or four times in the night was just old man’s trouble. Still,” he added, “most people spend their life worrying that they are going to get cancer. I don’t have to worry any more, do I?”

And Bob was a worrier. From a young age, family deaths, financial worries and a perennially troubled football club close to his heart, all contributed to it.

“Yes he was,” says Jean, when I remind her. “He was always fussing around the kids, telling them to be careful. And I still hear his voice today when I am crossing the road.”

The cancer responded to chemotherapy and radiotherapy only to prolong his life but not to cure him. He still attended home games over the last year of his life but couldn’t travel away, partly through tiredness and partly through embarrassment at needing toilet facilities so often.

“He was such a clean man. Such a clean man,” says Jean. And a proud one.

Towards the end, he underwent blood transfusions at Dorset County Hospital in Dorchester. While there, the unpopular George Rolls came to tell him that he was renaming the stadium the Bob Lucas, to which Bob replied, typically, that he shouldn’t do that. It was some redemption for Rolls and fitting tribute for a man who would not last much longer. The transfusions were no longer working. Bob went home.

The end came on the night of August 12th, 2010. “I had just done some washing,” Jean recalls. “I went upstairs and he had gone to sleep. To be honest, I was really pleased for him. He had gone peacefully, without any pain.”

I felt humble in Jean’s company, inadequate when I contemplated their collective acceptance of life’s cruelties and the club’s insensitivities.

That first game after his death, the night I wept as I hugged her, I ran into an old club official who had once carried out an edict from a crass chief executive that she was no longer allowed into boardroom or directors’ box on match days. I lost my temper, expressing my contempt for him and his old boss.

There was no such bitterness from Jean or Bob, hurt as they were by it. Both bore the trials of the football club, and the tribulations it caused them, with stoicism.

My doubt that I would be so forgiving was one reason why I did not attend the funeral. I did not want to encounter men who had been unkind to Bob, goaded into speaking out at the sight of them, and so potentially mar an occasion that would become so big that Jean had to hire the Ocean Ballroom of the town’s Pavilion Theatre to accommodate all the well-wishers.

“I was going to ask you to speak at the funeral,” says Jean now, and for a moment I feel sad, guilty even, that I hadn’t attended. Then I felt grateful to be a writer given a privileged opportunity to spill the contents of his heart.

Jean’s gratitude is at having spent such a contented married life with Bob and shared his passion for a game and a club that may have beset them with angst but also gave focus and meaning to their lives.

I press her. Come on, I say, no-one is that good, no couple that happy. Surely he got angry, surely you argued?

“Well, there were times when I might have done something he didn’t agree with, or the other way round,” she says. “Then it would go quiet for a while. In the end, he would say something like, ‘What do you want for tea?’ We never got too upset about anything really.”

Apart from the football club. “I still think of Bob up there looking down on another crisis at the club and saying, ‘not again.’ He used to say ‘that club made me more ill than the cancer.'”

Jean was still looking down on the football these days from her seat in the main stand – first-team, reserves and the women’s team – as she approached her 80th birthday. A local taxi firm was generously taking her to games for nothing. And like everyone else, she looked beyond current Southern League travails and hoped for better days for the club now that it was back in the ownership of Trustees – one of which she had been asked to become – rather than one man.

She was getting used to being on her own, she said, as she had done at times during Bob’s life. “I was a bit of a football widow,” she says. “Bob was working, then away with football at weekends. Well, you know what it’s like.”

Apart from weekly trips to the stadium that bears her husband’s name, she kept his memory alive by repeating the walks along the seafront that Bob loved so dearly, always feeling himself lucky to have lived in Weymouth. She made a point of getting out every day, she added, even if it was just to go and get a copy of the Echo.

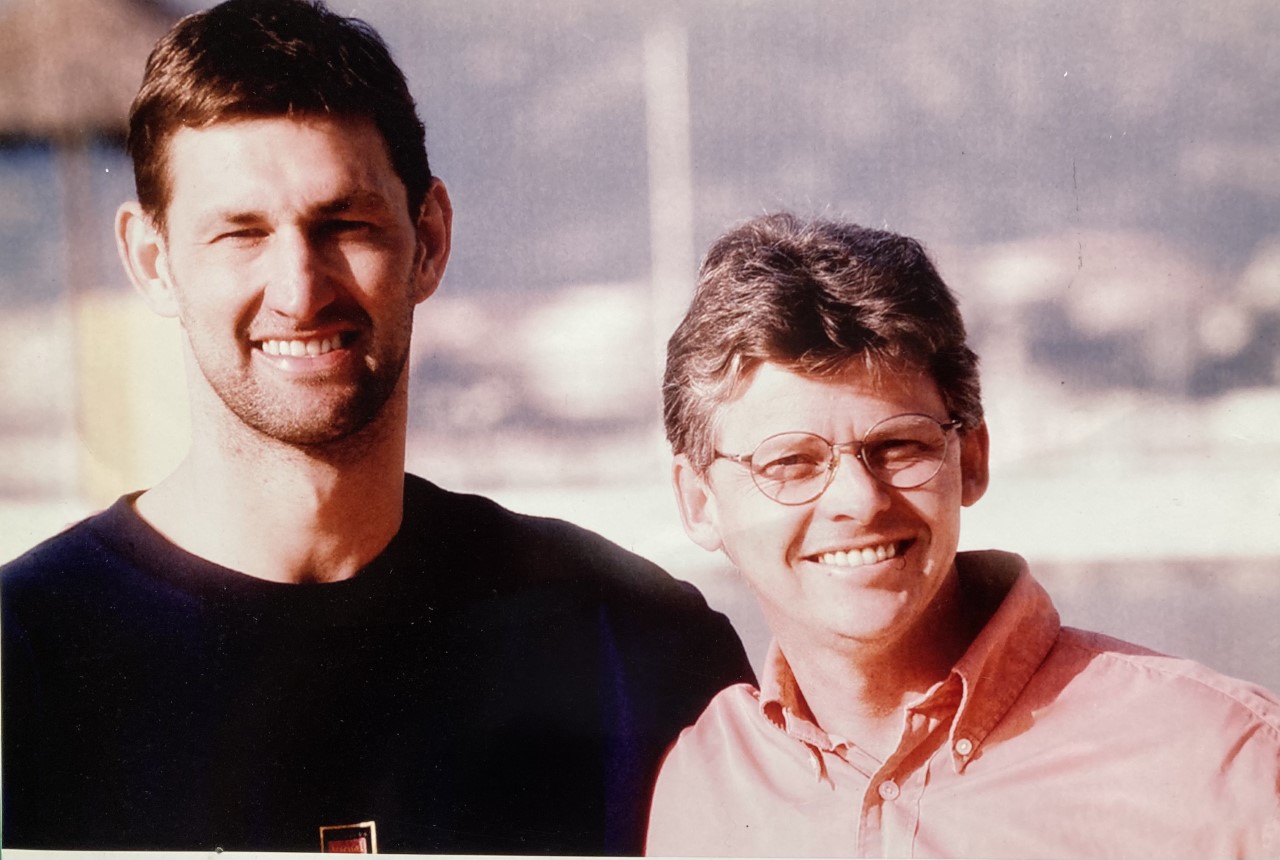

Jeans offers me a cup of tea and as she goes to the kitchen to make it, I take the chance to use the upstairs toilet. There on the landing is a framed picture of myself and Steve Claridge – who called him “the nicest man in the world” – with Bob in the middle, our arms around him. I remembered the occasion. It was the night we went top of the Southern League. I felt flattered, moved. Nowhere else in the house was there a picture of another chairman or manager.

“He always liked Steve, ever since he came to the club as a young player,” says Jean when I remark on it. “And,” she adds quietly. “He did think you were a good chairman.” Praise from the understated is always praise indeed.

Those in football often joke that the game takes years off your life. Actually, as the 85 of Bob Lucas’s show, for many it may well put years on life. You hope as the carrier of his torch, the same can be said of Jean Lucas. Over five decades, she enabled Bob to become the conscience and figurehead of the club. Now the club needed her presence as reminder, not least in how to be effective in working happily together.

The pair certainly enriched my life and enhanced Weymouth Football Club as they rose above its in-fighting to illustrate what is good in life, all that is good in the game – and could be again, as James Earl Jones said in Field of Dreams. Every club should have such a couple.

Leave A Comment