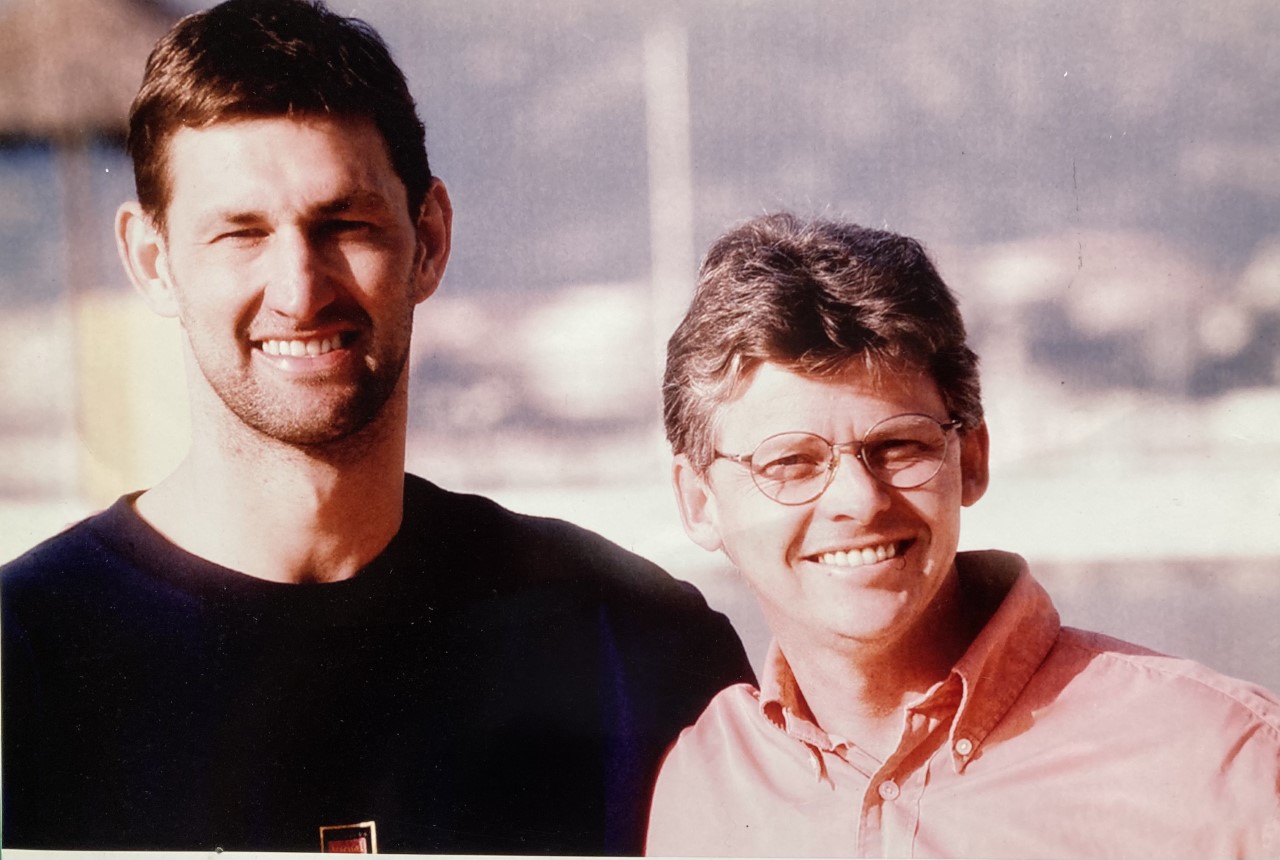

Floodlit Dreams publisher and author Seth Burkett is currently playing professional football in Sri Lanka. Throughout his time he’ll be blogging on the Floodlit Dreams website and writing a weekly column in the Non-League Paper. Below is an extract from his diary.

Have you ever heard of a doctor’s house that doesn’t have a washing machine? Neither had I. When I asked our coach Thaabit if I’d be able to wash my clothes regularly when I got to Sri Lanka, this isn’t what I had in mind. He told me yes, of course I would. Sri Lanka may be third world but they do at least have some basic hygiene standards.

What he actually meant, though, was that I’d have to stand in the hot garden – roasting at 84% humidity – with my sweaty clothes bundled together under the garden tap. A bar of detergent soap is in my hands. An army of red ants is crawling over my feet. I soak each garment then rub it with the soap, rinse it out, squeeze, then lay it on the floor to dry. The cycle repeats. It takes me ages.

It’ll be revolutionary once washing machines come to Sri Lanka en masse. But until then I’ll be washing my clothes with soap. It’s not exactly the life you imagine of a professional footballer.

*

Thaabit is in a great mood today. The disappointment of yesterday has been forgotten after this morning’s session. Again he dismisses it as team politics. But we probe deeper, and as we do so he opens up. He tells us it wasn’t just the fact that Mindron had stayed after Thaabit had banished him, but that he’d been hidden.

Despite his obvious talent, Mindron hadn’t made the cut for this week’s squad and had already been asked to leave for his inflammatory attitude, telling the other players that they were terrible and detailing how he had arrived to save them for the upcoming season. After being cut, he was allowed to return to the stadium to pick up his bags. Thaabit was furious when he saw that Mindron was still training, but assistant coach Kapuli assured him that Mindron just wanted a run about.

That night, Mindron instead stayed in the stadium dormitory. He stayed there the whole next day too. He wouldn’t have been found, either, if Thaabit hadn’t have come to his room to ask the masseuse to stay for longer.

Thaabit didn’t just get angry because Mindron was still there. Mindron is friends with the captain, Chinna. Their friendship outweighed Chinna’s loyalty to the coach, so Chinna agreed to hide Mindron’s presence.

As a result, Chinna has also been asked to leave by Thaabit. Unlike Mindron, he wasn’t up for hanging around. The pair are already back in Trincomalee. Thaabit still plans to speak to the captain and ask him to be part of the squad, but he also has plenty of options to cover Chinna’s position.

Chinna struck me as a proper captain. Hard working, respectful and always leading by example, he’s the kind of person you want in your team. He’s loyal. But it seems he’s more loyal to his friends than his football. Who can blame him?

With the respect that he commands in the changing room, Thaabit is aware that the Mindron situation could lead Chinna to turn a number of players against his leadership. It’s a delicate situation which requires delicate handling. I don’t envy Thaabit one bit.

*

My body is sore but not injured. My mind is drained but still working. My lip, however, is bleeding heavily. I’ve just received my first bad challenge in Sri Lanka and it hasn’t come from a Sri Lankan.

Excited by the prospect of a goal, Dean swung his arm out to hold me off at centre back. As he did so his elbow caught my lip. It worked. I went down and Dean rolled me. There’s no apology and there’s no need for one. We both understand it was just one of those things that happens when you play football.

The Sri Lankans treat it as GBH. My teammates insist the game be stopped. Sakhti sprints to get me some water. The incident motivates them further.

The standard is much higher today. Yesterday I could run with the ball at will. Now I’m being hounded by Priyan, Banda and Dean. I barely get a second to think. Our team is also playing with intensity. Everyone desperately wants to prove themselves.

Thaabit has been clever here. He’s kept the players on their toes. Now he’s clearly split the teams to play his first choice defence against his first choice attack. It makes for an even game. We’re up against it as wave after wave comes at us, but whenever we do get to make a forward pass it slices through our opponent’s defence at will.

With the score at 2-2, Thaabit orders us to play the game on the full pitch. We’ve been trying different formations throughout and now he wants my team to play 3-4-3. He tells me to set up my team as the captain. I hold total responsibility for what happens. Thaabit wants me to take all of the free-kicks, tell the players where to stand and even take the goal-kicks.

I’m not used to this. It’s like I’m the manager’s son in a Sunday league side.

We concede within ten seconds. From the kick-off the ball is played to Azil at right back. He makes a hash of passing forward, then gives a hospital pass to Aflal in centre midfield. With Dean snarling down his neck, Aflal shouts ‘Seth’ and aims a pass in my direction. He aims, but he doesn’t execute. The loose ball falls to Banda who gleefully strikes home.

20 seconds later it’s 1-1. The same thing happens at the other end. This is my first experience of Sri Lankan football on a full sized pitch.

The mistakes settle down. The team that makes the fewest will win. Dean and Banda are pulling me all over the place but aren’t being played the right balls. We’re on the front foot. Our long balls are coming off. The only player on the other team who heads the ball is Dean, and he’s usually at my side. We score from a long ball, then score again. It ends up being a comfortable if not deserved victory. Dean is left to rue the state of his team’s defence.

Several players head home after the session. Balaya, Chinna’s brother and my defensive partner, says his goodbye. When I tell him that I’ll see him in Trincomalee he looks evasive. A post training discussion is being held on the pitch by the senior players who are most friendly with Chinna. They’re there for half an hour.

This doesn’t seem right. A storm could be coming.

*

Me and Dean have discovered the supermarket. There’s shelves and shelves of beautiful, glorious, refined sugar. Dean goes crazy. He gets two ice creams, a bottle of Sprite, two tubes of Pringles and a packet of Maltesers. I get a Fanta, a bottle of water and a Mars bar. Our bodies are being pushed to the limits, they deserve a treat.

Hizam and Rojan stumble across us in the aisle. Hizam stares at our sugary snacks.

‘Coach say no fizzy drinks,’ he tells us. We reply that it’s ok. He smiles and disappears. The next minute he’s standing behind us in the queue with a bottle of Coke and a tube of Pringles.

I curse myself. The reality is that our teammates look up to me and Dean. Hizam does everything I tell him to on the pitch and is always grateful for any direction. Our teammates are impressionable and see us as role models, which feels crazy. I’m not used to this.

I feel so guilty that I put my Mars bar back on the shelf and get a banana instead.

I keep the Fanta.

Leave A Comment